Source: Eusebius.Holmes@icloud.com. Join the Inclusive Competition Forum (“ICF”)

CL is not be part of the problem, BUT part of the solution.

EU LAW

Article 101 and 102 TFEU and merger control under the European Merger Control Regulation (“EUMR”).

We face a ‘climate emergency’ in which a rapid move to more sustainable development is vital. Tragically, there is clear evidence that fear of competition law is having a chilling effect on urgent and necessary cooperative action by companies to fight climate change. This is particularly the case where a company acting unilaterally would incur increased costs which it could not recoup and would thus incur a “first mover disadvantage”. For example, if one car manufacturer increases its emission standards; one washing machine manufacturer increases the energy efficiency of its machines; or a light bulb manufacturer phases out bulbs with a short life, these initiatives are not viable if only done unilaterally by individual firms. Of course, it is not always necessary for firms to cooperate. Where the goal could be met equally well by unilateral action, then cooperation would not be justified (this is the “proportionality” principle or “no more restrictive than necessary” rule). However, given the urgency of action to fight climate change, the burden is on companies to show that cooperation is necessary.

It’s not so much the law that needs to change but our approach to it.

(“TFEU”) Article 11: “Environmental protection must be integrated into the definition and interpretation of the Union policies and activities, in particular with a view to promoting sustainable development.”. This applies also to competition law.

Article 37 of the EU Charter on Fundamental Rights essentially repeats this: Agreements promoting sustainability need not be caught by Article 101 TFEU

[Albany International BV v. Stichting Case C-67/96. ECR 1999 1-05751], the (“ECJ”) decided that Article 101 does not apply to collective bargaining.

Abuse of Dominant position (ADP)

Article 102(a) prohibits (as an abuse) all “unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions” of a dominant company. Since the categories of abuse (under Article 102) are not fixed, it could not be used to attack company practices unfair from an economic, political, social, environmental or moral point of view.

Example: use 102.a to challenge the gov policies, cta decisions, ftc decisions via Judicial Review on the depressingly low prices paid by some retailers to farmers.

While some companies do engage in “green washing”, there are companies (and directors) genuinely trying “to make a difference”. Competition law should not make it more difficult to put these good intentions into practice.

There are five ways in which sustainability should be considered to assess the legality of mergers:

- In the assessment of the merger under Article 2 of the (“EUMR”);

- When considering “efficiencies” under the EUMR;

- When considering “remedies”.

- Under Article 21(4) of the EUMR; and

- When mergers are reviewed under national competition law.

While there are good social reasons for supporting some producers, there is also a sustainability angle. Low prices encourage an excessive use of scarce resources and some low prices (eg for bananas, coffee or cocoa) are discouraging many sustainable land use practices.

UK law

The Legal Framework: For antitrust: the CA ’98, and for mergers and market investigations: the Enterprise Act 2002 (“EA ‘02”)

Under EU law, the equivalent provisions (Article 101 and 102 TFEU), have to be interpreted and applied in accordance with the EU treaties which say that sustainability “must” be taken into account…..Unfortunately, there is nothing equivalent in UK law. The question therefore arises as to whether there are any other sources of law that might require climate change to be taken into account in applying UK competition law. Potential candidates: The UK Climate Change Act; the Paris Agreement on climate change and human rights law.

The Climate Change Act 2008

commits the UK government to:

-reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 100% (net zero) by 2050,

-to assess the risks and opportunities from climate change for the UK, and

-to produce a climate change risk assessment every 5 years.

The Climate Change Act does not have any “constitutional” status (unlike the EU laws) , thus it cannot (at least on its own) override UK competition legislation.

The Paris Agreement 2015

the EU (on behalf of all member states-which included the UK at the time), along with some 160 other countries, made pledges to reduce emissions up to 2030

The problem with the Paris Agreement is that it is an international agreement. But the UK has a “dualist” approach to international agreements. They only have a direct affect in UK law if translated into domestic legislation. Thus the Paris Agreement cannot (at least on its own) directly affect UK competition legislation.

The Heathrow Airport Decision

the Court of Appeal held that the government’s approval of a third runway at Heathrow airport was unlawful as the government had failed to take into account the Paris Agreement.

But this ruling applied only to planning law. Unfortunately, I am not aware of anything analogous in competition law.

Exclusion from the Competition Act

Exceptionally, the UK government can use their powers to exclude an agreement/s from the prohibition on anti-competitive agreements. This is where the relevant minister is satisfied that this is “appropriate” to “avoid a conflict between [UK competition law] and an international obligation of the UK”.

It is clear that the Paris Agreement (and other agreements relating to climate change) are international obligations of the UK16. It is also clear that competition law should not prohibit agreements which would make a substantial contribution to reducing UK emissions. Thus, circumstances may arise that would make exclusion of certain competition agreements necessary.

The Urgenda Decision

In December 2019, the Dutch Supreme Court held that the Dutch state was required to reduce, by the end of 2020, its emission of greenhouse gases by at least 25% compared to 1990. The court first recognised the “dire consequences” of climate change and that this “will jeopardise the lives, welfare and living environment of many people all over the world, including in the Netherlands”. Next it looked at (ECHR) Article 2 which protects the right to life, and Article 8 which protects the right to respect private and family life. Under the case law of (ECtHR), a contracting party is obliged by these provisions to “take suitable measures if a real and immediate risk to people’s lives or welfare exists and the state is aware of that risk”. This includes “environmental hazards that threaten large groups or the population as whole, even if the hazards will only materialise over the long term”. Furthermore, Article 13 ECHR requires national courts to provide effective legal protection. The Dutch Constitution required the Dutch Courts to apply the provisions of the ECHR in accordance with the interpretation of the ECtHR. The supreme court upheld the Dutch court of appeal’s judgment that the state’s policy on greenhouse gas reduction “is obviously not meeting the requirements pursuant to Articles 2 and 8 ECHR to take suitable measures to protect the residents of the Netherlands from dangerous climate change”. The Dutch government was therefore ordered to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25% by the end of 2020. How it does so is up to it.

ANTITRUST-AGREEMENTS AND ADP

UK law does not have “constitutional” provisions on sustainability, unlike EU law. But this does not mean that UK antitrust law (or any other UK law) can breach sustainability. Why?:

- Chapter 1 prohibition on anti-competitive agreements and Chapter 2 prohibition on abuse of dominant position in the CA ’98, are identical to Articles 101 and 102 TFEU.

- Although Articles 101 and 102 must be interpreted in the light of the constitutional provisions of the EU, they are based on general competition law.

Section 60 of the CA ’98:

requires the CMA ,other sectoral regulators, and UK courts to interpret UK antitrust law consistently with EU law. After the transition period the CMA and UK courts must ensure that there is “no inconsistency” between UK competition law and pre-Brexit EU competition law. However, Post-Brexit, there are good reasons to expect that the interpretation of UK and EU provisions in this area will remain very closely aligned on sustainability. In particular;

-

- UK courts regularly look for inspiration from other legal systems;

- In this case the relevant legal provisions are identical;

- In many instances the particular issue may be looked at by both the UK and EU authorities in “parallel proceedings” (and they will often co- ordinate their investigations); and

- Most competition officials and many UK judges have spent their professional lives steeped in EU law and will not quickly “unlearn” their EU heritage (the present author being but one example).

MERGER CONTROL

Ways to protect sustainability in UK merger control

1-EU LAW

While EU and UK competition law on agreements and abuse of dominance (considered above) are nearly identical, there is a greater difference in merger laws.

1- The key test under the EU merger control regulation (“EUMR”) is whether or not the merger is likely to result in a “significant impediment to effective competition” (“SIEC”). But, under UK law the key test is whether or not the merger is likely to result in a “substantial lessening of competition” (”SLC”). But, in practice, in most cases they are identical

2- there is no equivalent requirement in UK law, to Article 2(1) (b) of the EUMR: the requirement that the development of progress must be to the consumer’s advantage and never an obstacle to competition.

3-the EUMR (like the antitrust rules above) is grounded in the constitutional provisions of the EU treaties for which there is no direct UK equivalent .

After the transition period, in many instances, both the EC and the CMA, will be investigating the same merger in “parallel proceedings”, and exchanging ideas and information on the deal, thus influencing each other.

2-Quality and Innovation.

competition on quality and innovation is key to sustainability. For example, if a merger is likely to lead to the production of more sustainable products (eg less polluting products or goods using fewer natural resources) then those goods can be seen as being more innovative and of a higher quality.

CMA: para 1.16 of its “Merger Assessment Guidelines”: “the CMA assessment is similar to the EC’s. See for example the Bayer/ Monsanto merger discussed in “Competition Merger Brief” (2018) 2/2018 6.

3-Efficiencies

CMA : “efficiencies arising from a merger may enhance rivalry, with the result that the merger does not give rise to an SLC (substantial lessening of competition)”. For example, if the merged entity can produce using fewer natural resources, that is a clear “efficiency”.

4-Relevant Customer Benefits

The CMA may decide not to open a merger investigation if: ” relevant customer benefits outweigh the lessening of competition and any adverse effects of such lessening”. Such ‘relevant customer benefit’ must result in either:

- “lower prices, higher quality or greater choice of goods or services in any market in the UK “; or

- “greater innovation in relation to such goods or services”

“Relevant customers” includes future customers This is crucial, as the benefits will be felt, not only by us but by our children and grandchildren; BUT refers only to the customers of the merged company.

5-PI

Under the EA ‘02, the government can intervene in a merger where certain “specified” “public interests” are at stake. The minister takes the decision as to whether the CMA conducts an investigation and whether to block or clear the merger, either conditionally or unconditionally-in each case on the advice of the CMA.

The “specified considerations” of public interest are set out in Section 58 of the EA ‘02. At present the only one of relevance to sustainability is “national security”. This might for example capture considerations of sustainable energy supplies. However, in most cases where a merger raises sustainability concerns, the public interest concerns are unlikely to be relevant, meaning that the UK government would have no power to intervene.

6-Remedies

where the CMA finds that a merger has resulted (or may result) in an SLC, it is “required to decide whether action should be taken to remedy, mitigate or prevent the SLC ,or any adverse effects resulting from the SLC”

Thus, to protect nature we could request be be included, in the remedy package, measures to counter a merger’s negative effects on the environment.

The CMA can either take action itself or recommend that action be taken by government, regulators or other public authorities, such as local authorities or the Environment Agency.

MARKET INVESTIGATIONS (MIRs)

The other area where UK competition law differs from EU competition law, is in the possibility to carry out market investigation references (“MIR”s) and take remedial actions following them. MIRs are a flexible CMA power to determine which is the most appropriate course of action. There are 3 main points in market investigations:

1-The “AEC” ( adverse effects on competition) test:

The UK market investigation regime allows the CMA:“to assess whether competition in a market is working effectively, where it is desirable to focus on the functioning of the market as a whole, rather than on a single aspect of it, or the conduct of particular firms within it”.

This CMA power has been extended to carry out “cross-market” investigations, where the “sources of consumer….detriment may affect competition adversely across multiple markets”. This is a very flexible tool and allows the CMA to investigate features of markets which may give rise to anti-competitive effects industry wide, to tackle adverse effects on competition (AECs) from any source”.

Example: the failure of prices to reflect true costs of production ( by excluding so-called “externalities”) could distort competition between competitors. For example, a company using green energy may be bearing 100% of its energy costs, whereas its competitor using a “dirty” fuel is off loading some of its costs onto society. This is an example of a non “well-functioning market” in which competition is distorted.

2-Public Interest

A minister can also ask the CMA to look into certain “public interest” considerations, besides the competition issues. This gives the UK “the option to look across markets, rather than having to create independent inquiry bodies”.

Furthermore the minister has powers to appoint a public interest expert to advise the CMA. This might be, for example, someone from the Environment Agency or the Committee on Climate Change.

But this CMA power only applies to “specified” public interest considerations. At present the only one specified is national security. While this may exceptionally be relevant (eg in relation to energy supply).

3-Remedies.

The CMA has a wide range of options after a market investigation. These options are much wider than after an antitrust or merger investigation. Not only may the CMA make orders or accept undertakings under its competition powers, but it can use its consumer protection powers or make recommendations that remedial action be taken by others such as government, regulators and public authorities. This latter option may often be relevant where sustainability are concerned.

it is fear of competition law which stands on the way of vital action by business to fight climate change. Commissioner Vestager: “business can better respond to that demand [for more sustainable products], if they get together”.

There are 2 strands to the cl “relaxation” in the face of a crisis:

1-CMA’s Approach:

CMA: “coordination between competing businesses, if solely to address concerns arising from the current Covid crisis and does not go further or last longer than what is necessary, the CMA will not take action against it”….One only needs to replace the words “Covid -19 pandemic” to “climate crisis” ,and you have a draft blue print for valuable guidance to businesses trying to fight climate change. Measures to fight climate change should also be “no more restrictive than necessary” and, indeed, should not “last longer than is necessary to deal with these critical issues” (it’s just that, sadly, this time period is likely to be much longer than Covid).

2- Exclusion from UK competition law ( Section 9 CA ’98 , or Article 101(3) EU)

The CA ’98 : some company agreements are excluded from Chapter 1 (Prohibition on anti-competitive agreements) where the relevant minister is satisfied that there “are exceptional and compelling reasons of public policy why the Chapter 1 prohibition ought not to apply”…For instance, this exclusion was used to ensure the supply of food, during covid.

CL as an obstacle to sustainability ?

Cooperation agreements between businesses are subject to competition law scrutiny. Broadly speaking, EU competition law (as well as the national competition law regimes in the CEE/SEE region) prohibit agreements between businesses which harm competition. However, these same competition law regimes also provide for an exemption if such agreements produce benefits which outweigh the harm.

Many cooperation agreements between businesses which pursue environmental objectives will not harm competition and are therefore lawful. Certain environmental agreements between competitors may however have anti-competitive effects, e.g., when they lead to a price increase due to higher production costs. For such an agreement to be lawful, the parties to the agreement must show that the agreement produces benefits which outweigh its harmful effects on competition.

In recent years, the European Commission has been increasingly criticized for an unnecessarily narrow interpretation of the conditions under which environmental agreements may be exempted from the prohibition of anti-competitive agreements.

The EC’s 2004 Exemption Guidelines and its 2010 Horizontal Cooperation Guidelines have been widely perceived as excluding non-economic public policy goals such as environmental protection from the scope of the benefits that can be taken into account when weighing anti-competitive effects and the benefits of a cooperation agreement. The general perception of the European Commission’s guidelines has been that environmental benefits are only relevant when and to the extent that they benefit the customers of the products in question. On the other hand, benefits to society as a whole (so the conventional wisdom went) should not be taken into account.

As climate change becomes increasingly regarded as an existential threat, both the European Commission and many national competition enforcers are rethinking their approach towards those cooperation agreements which aim to contribute to environmental goals. This is an encouraging development.

The EC is currently reviewing its Horizontal Block Exemption Regulations and its 2010 Horizontal Cooperation Guidelines. In the public consultation on the evaluation of these regulations and guidelines (which ended in February 2020), a substantial number of businesses have called for clearer guidance on when environmental agreements between competitors do not infringe EU competition law. We expect the European Commission to provide such guidance in revised Horizontal Cooperation Guidelines.

The Dutch competition authority published draft guidelines on sustainability agreements for consultation in early July 2020. These draft guidelines propose a broad interpretation of the exemption conditions under Dutch competition law. This would enable the Dutch antitrust watchdog to balance anti-competitive effects of certain environmental agreements against benefits resulting from the agreement for society as a whole (e.g., a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions).

The Austrian legislator is currently considering whether the objective of a sustainable and climate-neutral economy should be explicitly mentioned in the Austrian Cartel Act. This would make it easier for the Austrian competition authorities to consider this objective in the assessment of environmental agreements. Furthermore, many competition enforcers in Europe have expressed their willingness to provide individual guidance to collaboration initiatives that pursue environmental objectives.

Climate change and the green transition will continue to be high on the political agenda of the European Commission and most national governments in Europe. This will also have an impact on how competition authorities will assess environmental agreements between businesses in the future. We expect competition enforcers to attach increasingly more weight to environmental objectives when balancing the anti-competitive effects and the environmental benefits of cooperation agreements.

This would be a welcome development as companies should no longer have to refrain from the legitimate collective action urgently needed to fight climate change due to the risk of competition enforcement. With careful planning, many collaboration initiatives which genuinely aim to contribute to environmental objectives can be structured in a way which will allow companies to tackle climate change without breaking competition rules.

CMA AND ENVIRONMENTAL LAW

The CMA has produced this information sheet to help businesses and trade associations better understand how competition law applies to sustainability agreements and where issues may arise.

When we refer to sustainability agreements in this document, we are referring to cooperation agreements between businesses (including industry-wide initiatives and decisions of trade associations) for the attainment of sustainability goals, such as tackling climate change. For example, businesses may decide to combine expertise to make their products more energy efficient or agree to use packaging material that meets certain standards in order to facilitate package recycling and reduce waste.

Sustainable development goals can include a wide range of objectives in addition to dealing with climate change. The CMA’s current focus is on the environmental aspect of sustainability agreements, particularly given our strategic priority related to climate change.

Supporting the transition to a low carbon economy is a strategic objective for the CMA. As part of our work in this area, the CMA wants to ensure that competition policy does not create an unnecessary obstacle to sustainable development and that businesses are not deterred from taking part in lawful sustainability initiatives in the mistaken belief that they may breach competition law.

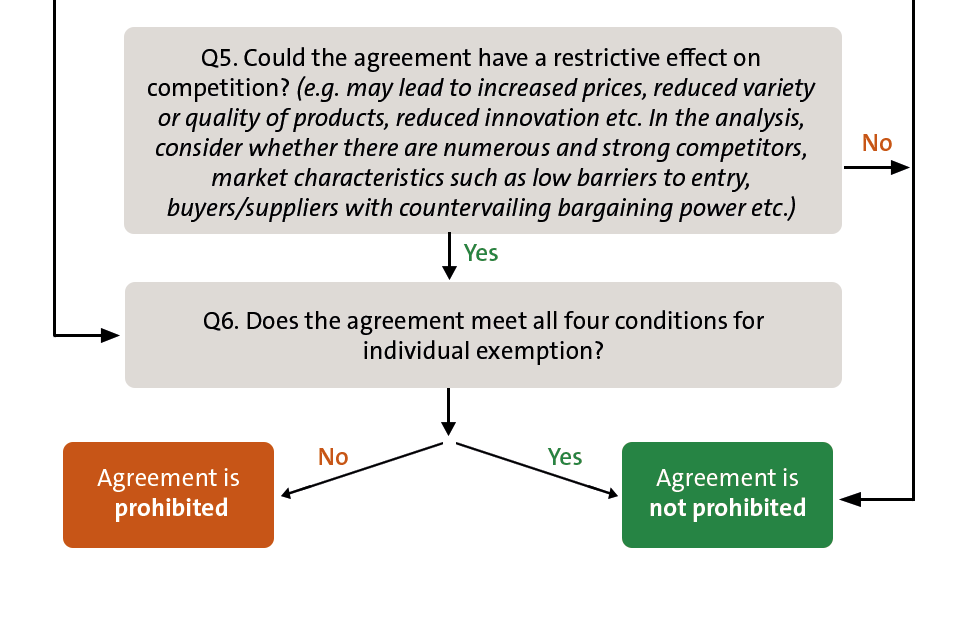

Competition law issues are most likely to arise where cooperation significantly restricts competition. However, even then an agreement must be assessed in its economic context and, in some cases, sustainability agreements may deliver benefits that outweigh the potential consequence of restricting competition.

In these cases, some exemptions from competition rules may be possible – either by meeting the requirements of an individual exemption or if an agreement falls into an existing exemption category.

Cooperation agreements between businesses which may restrict competition, will need to be considered on a case by case basis. We always recommend you seek independent legal advice to help you determine if your agreement could fall under an exemption or not.

The CMA recognises that collaboration can help achieve sustainability goals. However, sustainability agreements must not be used as a cover for a business cartel or other illegal anti-competitive behaviour.

The consequences of breaching competition law are serious and, therefore, it is important you are aware of the types of anti-competitive behaviour to avoid, including the exchange of any competitively sensitive information, especially on prices and output plans.

Seek independent legal advice

If you don’t have access to legal advisers, turn to the Competition Pro Bono Scheme. This scheme offers an initial free legal consultation. Other legal advisers may also offer advice on a similar basis.

Many sustainability agreements are standard-setting agreements by which businesses, often through trade associations or standardisation organisations, set standards on the environmental performance of products, production processes, or the resources used in production.

When setting up a new standard, businesses, trade associations and/or standardisation organisations should follow these steps to comply with competition law:

- allow stakeholders to inform themselves effectively of upcoming, on-going and finalised standardisation work in good time at each stage of the development standard – for example, through the publication of regular updates in dedicated journals

- guarantee that all competitors in the markets affected by the standard can participate in the standard-setting process and join the agreement

- ensure access to the standard is on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms for all businesses which comply with it

- if the standard-setting involves intellectual property rights (IPR), participants must disclose in good faith their IPR that might be essential to the implementation of the standard. They must also offer to licence their essential IPR to all third parties on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms. This should be provided for in an IPR policy from the standard-setting organisation

- ensure that the members of a standard setting organisation remain free to develop alternative standards (including higher standards) or products that do not comply with the agreed standard

When setting standards, businesses, trade associations and standardisation organisations should not:

- exchange or disclose commercially sensitive information that goes beyond what is necessary for setting the standard

- impose obligations (either directly or indirectly) to comply with the standard, label or code of conduct on businesses that do not wish to participate

- make it difficult for businesses to develop alternative standards (including higher standards) or products that do not comply with the agreed standard

- use quality norms to prevent a technology or a competitor from entering the market. Examples include (a) setting a standard and putting pressure on third parties to prevent them from marketing products which do not comply with that standard, or (b) colluding to exclude a new technology from an already existing standard

Avoid breaching CL

‘By object’ restrictions

There are certain forms of collusion between companies which by their nature are most likely to prevent, restrict or distort competition.

These practices are usually referred to as ‘by object’ restrictions and include price fixing, output limitation, the sharing of markets and customers, and bid rigging.

You must avoid these ‘by object’ restrictions in your sustainability agreements as they are almost always incompatible with competition rules.

In particular, you should be aware that:

- agreements containing one or more ‘by object’ restriction cannot benefit from the safe harbours provided for agreements of minor importance or block exemptions (see information on market share size)

- agreements containing ‘by object’ restrictions also typically would not qualify for individual exemptions.

Business cartels

Sustainability agreements must never be used as cover for a business cartel.

Cartels are the most serious form of anti-competitive behaviour between competitors. A business cartel exists when rivals agree to act together, instead of competing with each other, in order to benefit cartel members.

In such arrangements, participants normally agree to use one or several ‘by object’ restrictions listed above (i.e. agree to fix prices, share markets, rig bids or limit output), usually in order to preserve or drive up prices while maintaining the illusion of competition.

Such arrangements are illegal and the consequences of engaging in them are serious. Those caught breaking the law can face significant fines, director disqualification and in the most serious criminal cartel cases, prison.

Therefore, it is important that businesses expressly distance themselves from any situation where they suspect that sustainability issues are being used as a cover for anti-competitive practices.

Sharing sensitive information

You must always avoid exchanging competitively sensitive information directly with current or potential competitors, especially on prices and output plans. Doing so, even at a single meeting, can be a breach of competition law with serious consequences for the businesses involved.

Competitively sensitive information covers any non-public strategic information about a business’s commercial policy. It includes, but is not limited to, future pricing and output plans.

Historical commercial information (generally older than 3 years) is less likely to be sensitive, particularly if individual businesses’ commercial activities cannot be identified in it, in other words when the information is aggregated.

It is sometimes acceptable for businesses to share competitively sensitive information (for example recent information on capacities, sales or cost of inputs and components) with a third-party such as a trade association or market intelligence firm to create aggregated market-wide statistics that may be beneficial to suppliers, customers and other market participants by allowing them to get a clearer picture of the economic situation of a sector. However, third party providers collating the data must be careful not to disclose received individualised information back to businesses competing on the market and not to use it to facilitate coordination between competitors.

Consider available allowances and exemptions

Assess the size of your market share

If the combined market share of the businesses involved in a sustainability agreement is below a certain threshold, the agreement may benefit from special competition law allowances.

Various competition law guidelines identify market share thresholds (or ‘safe harbours’) for different types of agreements. It is generally considered that an agreement would not breach competition law if the market shares of the businesses involved do not exceed the relevant threshold and the agreement does not create any serious competition restrictions (for example, price fixing, market sharing, bid rigging etc – also known as ‘by object’ restrictions).

Before you assess your market share, you need first to define what the relevant market is (both in terms of product and geography) and then assess your share of this in accordance with applicable guidance.

If you think your market share in the relevant market is low, you should consider seeking independent legal advice as to whether your sustainability agreement may benefit from the safe harbour provided for agreements of minor importance (de minimis) or the low market share thresholds set out for certain types of cooperation agreements:

| Agreement type | Market share threshold |

|---|---|

| Agreements of minor importance if parties are competitors (or it is difficult to classify whether parties are competitors or non-competitors) | The parties’ joint share on any of the relevant markets affected by the agreement is 10 %* or lower[footnote 3] |

| Agreements of minor importance if parties are not competitors | The market share held by each of the parties on any of the relevant markets affected by the agreement is 15%* or lower[footnote 4] |

| Joint commercialisation agreements (for example, joint selling, joint distribution, joint advertising and similar agreements) | The parties’ joint share of the relevant market is 15% or lower[footnote 5] |

| Joint purchasing agreements | The parties’ joint share on the purchasing market is 15% or lower and the joint share on the selling market is 15% or lower[footnote 6] |

| Production agreements[footnote 7] | The parties’ joint share of the relevant market is 20% or lower[footnote 8] |

(*) Note, that in some circumstances, the threshold mentioned above is reduced to 5%.[footnote 9]

There is no presumption that agreements where parties’ market shares exceed the indicated thresholds are in breach of competition law. The potential effect of such agreements and the benefits they may create will need to be assessed on a case by case basis. (See information below on meeting exemptions criteria.)

Consider whether your agreement meets the criteria for an exemption

Use existing exemptions where applicable

Some sustainability initiatives may fall into one of the general categories of agreements (such as research and development or specialisation agreements) which may be exempt from the anti-competitive agreements prohibition under what we refer to as a ‘block exemption’.

This means that if your sustainability agreement satisfies the conditions set out in the relevant Block Exemption Regulations it could be considered compatible with competition law despite its potential restrictive effects. These conditions include, among others, maximum market share requirements, and specific restrictions that the agreements should not contain or to which the exemption would not apply.

Businesses should seek independent legal advice if they think their agreement may benefit from an existing block exemption.

Agreements covered by the EU Block Exemption Regulations are automatically exempt from the Chapter I prohibition in the Competition Act 1998. Following the end of the Transition Period (31 December 2020), UK businesses continue to benefit from EU Block Exemption Regulations as incorporated into domestic law (‘retained exemptions’).

Demonstrate that the conditions for an individual exemption are met

Some agreements that appear to restrict competition, and do not fall under an existing block exemption (see above), may still be permitted on an individual basis provided they generate benefits which are deemed to outweigh the disadvantages of restricted competition.

If the agreement is likely to affect competition (for example, by leading to increased prices or a reduction in the choice of products on the market), you will need to be able to demonstrate that your agreement meets each of the following criteria for an individual exemption:

- the agreement generates efficiencies – for example, increases the quality of products

- these efficiencies cannot be achieved with other economically practicable and less restrictive means

- these efficiencies benefit consumers

- the agreement will not lead to the elimination of competition in the market

Businesses should seek independent legal advice on whether their agreement may qualify for an individual exemption.

FLOWCHART for Sustainability agreements or trade association decisions